Banned Book Club: 5 Of The Best Reads They Don't Want You To Know About

For a country so preoccupied with free speech, there sure are an awful lot of people voicing their thoughts on who shouldn't read what. It's tempting to think of banned books as remnants of a more censorious past, but the American Library Association's 2024 report suggests otherwise. In that year alone, more than 4,000 titles were challenged — largely by conservative pressure groups, elected officials, and ideologically motivated campaigns. In a political age so loudly invested in the idea of free speech, it's difficult to ignore that this isn't happening despite progress, but because of it.

These removals don't reflect a book's failure. It's quite the opposite. Bans and challenges are acknowledgements, however backhanded, of its clarity. The more precisely a book captures something real — be it a body, a belief, a blurred border, or a bias brought into focus — the more likely it is to vanish from a reading list. Ironically, you could almost build a better education out of the titles removed than the ones allowed to remain.

The language around censorship changes with the times, but not its instinct. Every banned book reveals something about the era or area that tried to silence it. And what this era ostensibly feels most afraid of is the brittle illusion that certain realities can be erased if they're never read aloud. History rarely repeats itself in the same words, but the same silence seems to always return.

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

In 2007, Toni Morrison wrote of "watching cultural exorcisms debase literature." What better description for the ongoing campaign to ban "The Bluest Eye"? First published in 1970, Morrison's debut was met with resistance from the start, and has been removed from classrooms with persistent regularity ever since. More than half a century later, in 2024, it still ranked third on the American Library Association's list of most challenged books. The stated objections remain familiar: "sexually explicit material" and "unsuitable for students." But such labels have always felt like a thinly-veiled sidestep of the novel's true transgression: its refusal to render genuine Black suffering palatable or peripheral.

Morrison's story of Pecola Breedlove, a young Black girl who prays for blue eyes, believing Whiteness will make her beautiful and loved, exposes just how deeply racism contorts the identities of those who bear its weight. It's a novel about incest, how structural violence makes such horrors possible, and how a society shaped by White structures leaves its children unprotected. That Morrison does so without invoking a White audience is perhaps what has always unnerved censors the most.

An early review commended Morrison's style but questioned her scope, cautioning that her subject matter — "the Black side of provincial American life" — was too narrow to place her among the great American novelists (as if there weren't already centuries' worth of novels chronicling the interior lives of White people). To call that project "narrow" is to reveal how little space Black lives have been granted in the literary world.

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

In Texas, a 2023 law signed by Republican Governor Greg Abbott banned books from school libraries deemed "patently offensive" by undefined community standards. This was a phrase vague enough to mean almost anything, and often used to mean one thing: queer. The legislation was just one node in a broader movement (spurred by parents' rights groups and partisan zeal) to sideline books that acknowledge LGBTQ+ existence.

This is not new. In Alabama in 2005, the effort was less coded. That year, state representative Gerald Allan proposed legislation that would prohibit public funding for any materials that "promote homosexuality as an acceptable lifestyle." Evelyn Waugh's "Brideshead Revisited," published in 1945, was explicitly named as an offending work.

Waugh's novel is not an ode to queerness. It is, in many ways, a book about repression, Catholic guilt, and the post-war disintegration of the English aristocracy. Charles Ryder, a painter-turned-officer who, on the eve of war, finds himself stationed at the crumbling estate of Brideshead. From here, he is haunted by the lush, melancholic recollection of his youth at Oxford and the intoxicating closeness he once shared with Sebastian Flyte. Their relationship drifts through champagne-soaked summers and into shadow, unmistakably intimate but never explicitly named.

This work has often been likened to "The Secret History" — one of the best thriller and mystery picks from the Read With Jenna book club. The novel itself is saturated with religious shame, its moral axis tilted more toward penitence than liberation. Even still, it continues to be read as subversive. If today's culture wars feel new, "Brideshead Revisited" reminds us it is not. The rhetoric evolves, but the impulse endures.

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

As its title would suggest, Ralph Ellison's "Invisible Man" is a novel about what it means to move through the world unseen. Not in the fantastical sense, but in the ordinary, daily way that race renders some people hypervisible and others conveniently overlooked. In 2013, a North Carolina school board voted to remove it from library shelves. A novel about erasure was, quite literally, erased.

Ellison offers the story of a young Black man making his way through society. The plot is episodic, often surreal. He moves through a series of institutions, where he reflects on the conditions that have rendered him invisible. The novel is deeply psychological and unapologetically difficult.

The complaint came from the parent of a student in the 11th grade, who found the book inappropriate, writing in a letter: "This novel is not so innocent; instead, this book is filthier, too much for teenagers." The board, in a 5-2 vote, agreed. One member remarked that he "didn't find any literary value" in the work, a verdict that might have carried more weight had the book not already won the National Book Award in 1953, beating heavyweights like Hemingway and Steinbeck in the process. The novel had been one of three optional choices for a summer reading assignment. Even that was too much.

After public backlash and national attention, the board reversed its decision ten days later. One board member, noticeably moved, cited his son's military service: "He was fighting for these rights. I'm casting a vote to take them away." The novel's unsettling truth is supposed to do just that: unsettle. This is proof of concept.

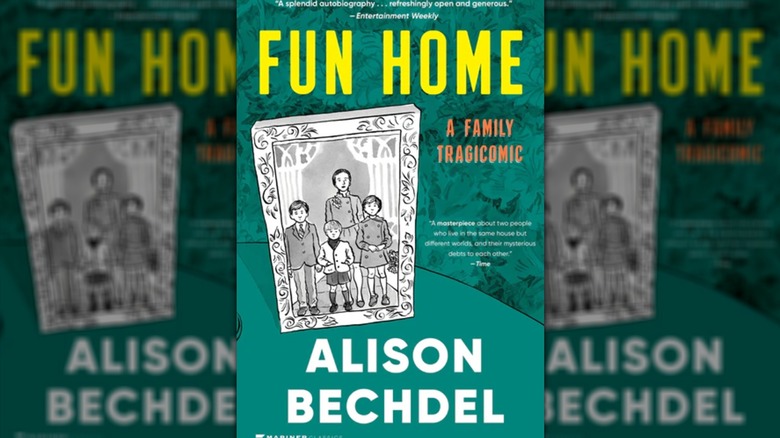

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

Eagle-eyed readers may know Alison Bechdel's name from the now-famous Bechdel test — the cinematic benchmark that asks whether a film includes two women who talk to each other about something other than a man. But after her name became a memeified metric, Bechdel started something just as radical.

"Fun Home," her 2006 graphic memoir, is one of those titles that would sit comfortably among books that will make you laugh, cry, and learn this Pride Month, or the must-read Sapphic books to add to your TBR. It traces Bechdel's coming-of-age in a small-town funeral home, her gradual understanding of her sexuality, and the shadowy presence of her father, a closeted gay man whose death may or may not have been a suicide. Its style is wry and cerebral, but its content — nudity, emotional trauma, sexuality — has become the basis for repeated attempts to ban it.

Since 2006, "Fun Home" has been challenged in school districts, libraries, and universities across the country. Critics often cite "graphic content" or "anti-religious sentiment," but beneath the stated concerns lies the more persistent discomfort toward depictions of LGBTQ+ lives. It was pulled from public libraries in Missouri, and other challenges — in California, Utah, and beyond — have pushed for parental consent requirements, or removed the book altogether, often with little fanfare.

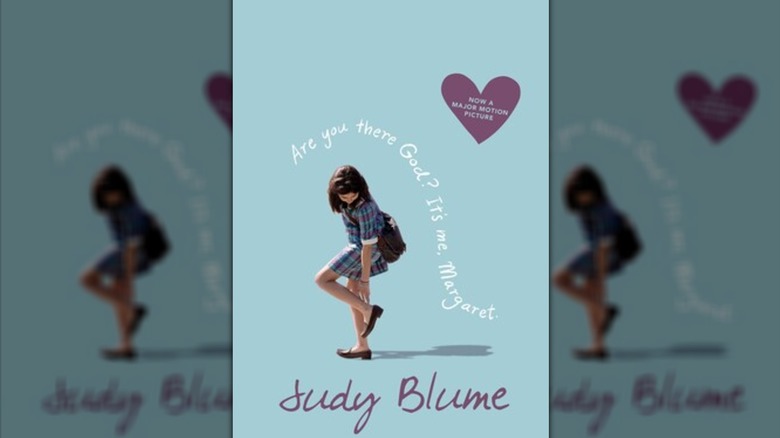

Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret by Judy Blume

The first time you read "Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret," you might be a nervous tweenager anticipating the arrival of your period. The second time, you might be older, and caught off guard by the book's willingness to say the things so many adults never could. Judy Blume's coming-of-age classic has been frequently challenged for what should be among its gentlest qualities: simply naming what girls go through as they grow up. Since its publication in 1970, it has been banned or restricted in classrooms and libraries for its open discussion of puberty, menstruation, and its portrayal of religion as something personal rather than prescriptive. In some cases, students have needed written parental consent just to check it out of the library.

At age 11, newly uprooted to suburban New Jersey, Margaret is sorting through the unspoken codes of girlhood, whilst wrestling with a more interior uncertainty: which religion, if any, should she choose? With a Jewish father and a Christian mother, Margaret has been left to find her own path. Her private conversations with God — always opened with the same tentative invocation — are the emotional spine of the book. So, too, are the scenes with her friends, who form a club to talk about "The Pre-Teen Sensations," complete with bust-enhancing exercises and anxieties about being the last to "get it."

The deeper resonance of "Margaret" hasn't changed. Even in adulthood, women return to the book for what remains scarce in literature: an honest rendering of girlhood doesn't beautify the already complex. This is a mirror of experience that's worth keeping in circulation.

How we chose the books

Every book on this list has been challenged or banned in the United States, but this is by no means a comprehensive record. With over 10,000 instances of public school book bans documented by PEN America in 2023-2024 alone, any attempt to capture the full scope of the best would be nearly impossible. Instead, this is a curated selection shaped by specific aims.

We chose books that speak, albeit in different registers, to the lives, questions, and tastes of our Women readership. Seeking to show our audience a range of topics and truths, we wanted the stories to reflect their lived experiences and also stretch them outwards. Finally, we also considered the craft. These are not just banned books. They are, quite simply, very good books. That, too, is part of why they've been challenged.